Funny What You Find in Your Wallet - Proust and 'A la recherche du temps perdu'

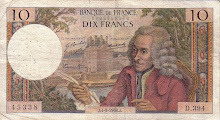

A clear out of your wallet can be quite a revealing and instructive experience. And sometimes an intense journey into the past.

One Mongolian train ticket - a single to Huhot, the capital, at 12.50 old yuan (then, ~$A2). Though I ended up sleeping on the floor, and under my seat, which had already been 'taken' by someone who managed to get into the carriage first - through the window.

One Mongolian train ticket - a single to Huhot, the capital, at 12.50 old yuan (then, ~$A2). Though I ended up sleeping on the floor, and under my seat, which had already been 'taken' by someone who managed to get into the carriage first - through the window.

One Paris Metro ticket, one of ten bought as a 'carnet'. On a day when I had change and didn't need to have my fare from a fellow-traveler.

One Maria Callas concert ticket, from when I was a kid living in London. From Dorothy C. who was an administrator at Covent Garden, and part of whose responsibilities included the box office. A moment of nepotism.

One business card of Miss Li Li, the grand-daughter of the last cook of Tzu Hsi (or Cixi), Dowager Empress of China and proprietress of 'A Homelike Restaurant: Chinese Court Cuisines'. Already posted.

One unused cheque from my central London Commonwealth Trading Bank account.

But most importantly, photos of 'my man'.

Wallets die and are superseded by their next generation. And these things obviously get transferred on. With the possibility of intense memory experiences one day! As that triggered by the 'petite madeleine' (a small plain cake) for the central protagonist in Marcel Proust's 'À la recherche du temps perdu' ('Remembrance of things past', 1923).

Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, save what was comprised in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, on my return home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump little cakes called "petites madeleines," which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted valve of a scallop shell. And soon, mechanically, dispirited after a dreary day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin.

...

And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom , my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it; perhaps because I had so often seen such things in the meantime, without tasting them, on the trays in pastry-cooks' windows, that their image had dissociated itself from those Combray days to take its place among others more recent; perhaps because of those memories, so long abandoned and put out of mind, nothing now survived, everything was scattered; the shapes of things, including that of the little scallop-shell of pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious folds, were either obliterated or had been so long dormant as to have lost the power of expansion which would have allowed them to resume their place in my consciousness.

...

And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom , my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it; perhaps because I had so often seen such things in the meantime, without tasting them, on the trays in pastry-cooks' windows, that their image had dissociated itself from those Combray days to take its place among others more recent; perhaps because of those memories, so long abandoned and put out of mind, nothing now survived, everything was scattered; the shapes of things, including that of the little scallop-shell of pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious folds, were either obliterated or had been so long dormant as to have lost the power of expansion which would have allowed them to resume their place in my consciousness.

I've had the past similarly triggered, but incredibly infrequently and perhaps without the intensity experienced by Proust. The author is however writing of a common enough human phenomenon - his readers do identify with such an event. So I long for another and try to remain always open to it. It's not just the memory of the details of the event and its unfolding that are addictive but the almost overpowering underlying and associated emotions.

![C18 Bronze Buddha [Southern China]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEioLkgVKuhDoIHQgM1X6Oe2hGn75yqaj4OJXPmNpumXmQPKxB22S57YS5DVrl1P7zl7BS6EFpAtaNZPze7gzVCRiQI54bwdHhVa4fGr7NOChZwTZoo92gUen6tC5U8gWIy_pv92U0FB38M/s1600/Buddha+%255BBronze%252C+C18%252C+China%255D+1.jpg)

+1998+Cropped.jpg)

Excellent read! Thanks!

ReplyDeletehey anon, been wanting to do this 'wallet' post for a while but wasn't sure on the take on it - then i realized the relation to Proust - and away it went! take care.

ReplyDelete